For many individual sports, such as tennis and road running, the summer season really starts in April. In triathlon, although still a relatively small sport and hence not organized as many other widespread sports such as tennis, cycling and soccer, the Belgian season always starts traditionally with a team triathlon on the first of May. Every year on that day, as a former triathlete, my thoughts still go to the days that it was my own turn to enter the arena and test the legs after a long winter preparation. Actually, I had a hate/love relationship with that race. It always has been a nervous day with too much attention and exposure for what it was worth according to me. In addition to the considerable importance for clubs, press and sponsors, the race was not really ‘a walk in the park’, but on the other hand too short for me to be ‘my cup of tea’ and the overall result was determined by the weakest link of the team (and not of yourself) in either swimming, cycling or running. This was why I always had mixed feelings when to decide whether or not – and if so, to what extent – to ‘taper’ for this event.

‘To taper’ means ‘to diminish, to decrease’. In the context of sports, ‘tapering-off’ implies decreasing the training load with the aim of performing better at the moment of truth. This is the principle of supercompensation: rest is a necessary part of the training process, to become stronger or faster; ‘the race is won in bed’.

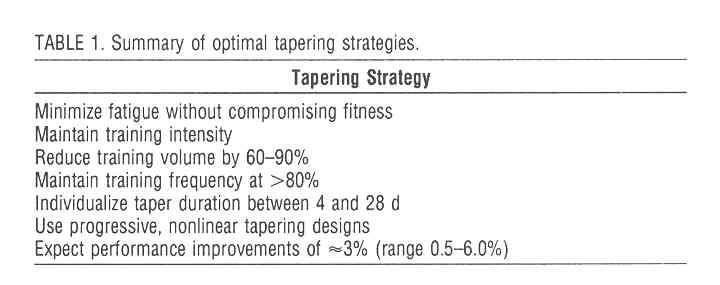

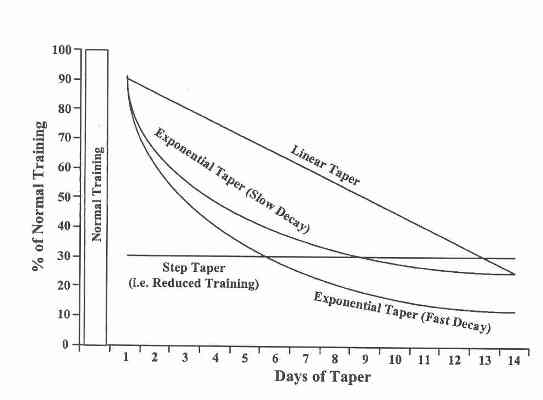

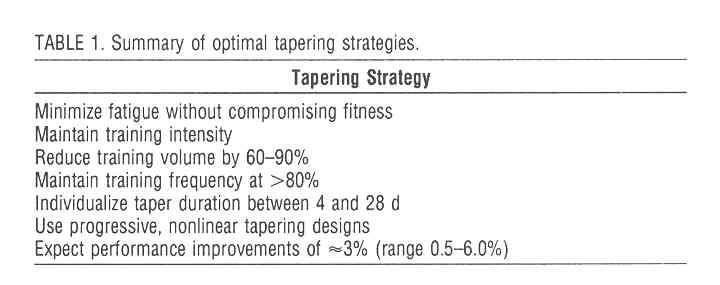

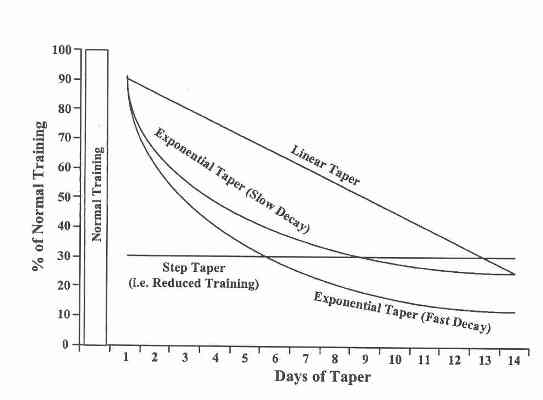

Decreasing the training load can be accomplished in several ways. Most important is to diminish training volume, i.e. the number of hours or distance of the training sessions. It is recommended to maintain a certain quality or intensity in the last training sessions: interval sessions are not forbidden, but fewer repetitions than in a regular training week are mandatory. A substantial reduction in the training frequency isn’t always necessary. Michael Phelps was told to still swim twice or even three times a day during the Olympic tournament, but only for very short sessions. In contrast, I have known amateur athletes who didn’t run at all during the last week preceding their marathon, but it is clear that this can not be the best way to ‘prepare’ your body and get ready for a serious effort.

A typical taper lasts 10 to 14 days. However, this depends not only of the type of taper or of the importance of the race, but mainly of the quantity and the quality of the training weeks by which the taper is preceded. If you completed a heavy training block of 3 weeks, you will certainly need 2 weeks to recover completely. If you were not able to train a lot in the last month before your desired peak moment, tapering-off for 4 days might do to perform at your very best. Nevertheless, as a general rule, it is a wise advice that ‘less is more’ in the last 10 days before major competition. You can do more harm than good by wanting to train too much in those last days. It should have happened by then…

(source: Mujika & Padilla, Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003)

No matter how perfect your physical preparation has been in the months before your D-Day, the last 48 hours are crucial. Especially eating – the ‘right’ things at the right time – can make it or break it during that timeframe. Although some guidelines hold true for everyone, this is often very individual and sometimes learned by trial and error. In this respect, but also from a mental perspective, I usually recommend to approach your race like a very heavy training session. Indeed, tapering-off is also about preparing the mind. However, make sure you know the difference between useful rituals and dysfunctional superstition. To date, there is no scientific evidence against sex or a glass of whine in the night before the race.

Kind regards,

Karel

#TrainHardButSmart

PS: the above picture dates back to May 1st, 2005 during the national team triathlon championship in Wachtebeke (BEL). Marino Vanhoenacker, current world record holder with 15 Iron Man victories, watches me during the run, wondering whether I’m still okay.

‘To taper’ means ‘to diminish, to decrease’. In the context of sports, ‘tapering-off’ implies decreasing the training load with the aim of performing better at the moment of truth. This is the principle of supercompensation: rest is a necessary part of the training process, to become stronger or faster; ‘the race is won in bed’.

Decreasing the training load can be accomplished in several ways. Most important is to diminish training volume, i.e. the number of hours or distance of the training sessions. It is recommended to maintain a certain quality or intensity in the last training sessions: interval sessions are not forbidden, but fewer repetitions than in a regular training week are mandatory. A substantial reduction in the training frequency isn’t always necessary. Michael Phelps was told to still swim twice or even three times a day during the Olympic tournament, but only for very short sessions. In contrast, I have known amateur athletes who didn’t run at all during the last week preceding their marathon, but it is clear that this can not be the best way to ‘prepare’ your body and get ready for a serious effort.

(source: Mujika & Padilla, Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003)

A typical taper lasts 10 to 14 days. However, this depends not only of the type of taper or of the importance of the race, but mainly of the quantity and the quality of the training weeks by which the taper is preceded. If you completed a heavy training block of 3 weeks, you will certainly need 2 weeks to recover completely. If you were not able to train a lot in the last month before your desired peak moment, tapering-off for 4 days might do to perform at your very best. Nevertheless, as a general rule, it is a wise advice that ‘less is more’ in the last 10 days before major competition. You can do more harm than good by wanting to train too much in those last days. It should have happened by then…

(source: Mujika & Padilla, Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003)

No matter how perfect your physical preparation has been in the months before your D-Day, the last 48 hours are crucial. Especially eating – the ‘right’ things at the right time – can make it or break it during that timeframe. Although some guidelines hold true for everyone, this is often very individual and sometimes learned by trial and error. In this respect, but also from a mental perspective, I usually recommend to approach your race like a very heavy training session. Indeed, tapering-off is also about preparing the mind. However, make sure you know the difference between useful rituals and dysfunctional superstition. To date, there is no scientific evidence against sex or a glass of whine in the night before the race.

Kind regards,

Karel

#TrainHardButSmart

PS: the above picture dates back to May 1st, 2005 during the national team triathlon championship in Wachtebeke (BEL). Marino Vanhoenacker, current world record holder with 15 Iron Man victories, watches me during the run, wondering whether I’m still okay.